Learning is enhanced when researchable questions are asked for which data are collected to infer towards conclusions.

- How does your learning objective become an inquirable question for pupils and students?

- How do you ensure that your teaching is perceived as relevant?

- How do you challenge students to think further?

- How do you activate and connect students’ interests to the subject matter?

- How can a pupil or student experience setbacks and successes?

… by guiding students in research design, implementation, and performance.

What does it mean and why is it important?

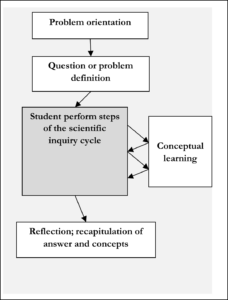

In inquiry-based learning, a pupil or student is encouraged to explore materials, ask questions and share ideas. The essence of inquiry-based learning, therefore, is that a pupil or student is actively engaged in seeking an answer to an research question, making observations to do so, analysing data, interpreting results and discussing conclusions. This can be done, for example, using the process shown in the diagram below. This enables them to build knowledge through exploration, analysis, and discussion.

Inquiry-based learning takes various forms, from simple to complex, guided to independent, prescribed to open-ended. Various teaching approaches can be used, including collaboration, discussion forms, and guided enquiry. Instead of memorising facts and materials, pupils and students learn collaboratively by doing and experimenting. Inquiry-based learning can thus essentially become a specific form of an authentic whole task that pupils and students can undertake. You, as a teacher, can start all teaching-learning activities with an inquiry task, in which pupils or students examine a part of the lesson material.

Part of the advantage of (guided) inquiry-based learning is that the pupils or students themselves actively engage with the concepts in a particular context, think about how to measure something, and how to interpret the results based on what you already know (their prior knowledge, or the literature, or a source book, such as encyclopaedia, BINAS and dictionary).

Often a counter-argument to inquiry-based learning is that it takes so much more time than ‘just’ explaining the subject matter. And it is true that inquiry-based learning takes time, precisely because pupils or students occasionally take a wrong turn, find out for themselves, look for another way and thus take their learning process into their own hands. Inquiry-based learning therefore has the advantage that a pupil or student actively processes the subject matter and its concepts, can place them in contexts, and becomes curious. Because they actively engage with the concepts themselves (theory) and practice (collecting data), the concepts will be linked to their prior knowledge and they can give a broader meaning to the subject matter. This will make that knowledge persist longer and be more easily transferable to other school subjects and other contexts.

Inquiry-based learning provides:

- Activation of relevant prior knowledge and skills;

- A mental capstone that gives meaning to the subject matter;

- Creative and critical thinking;

- Enhances intrinsic motivation, in part because pupils experience greater autonomy in formulating research question and method;

- Perseverance and experience of success;

- That pupils and students notice that they are already able to have innovative ideas;

- That pupils and students gain an understanding of how knowledge is created in their subjects and academic disciplines.

Below you will find two examples of courses which were adapted into inquiry based teaching; the old situation and the new situation are described. These new situations have included elements of inquiry-based learning in their courses.

Old situation narrative: History in secondary school

A History teacher first explains typical symbols in cartoons, the point of view of the cartoonist, and its relation to the time period and context in which it was drawn. On the knowledge test, students will be presented with some cartoons and will have to analyse them. In the coming lessons, this will be practised and each lesson the teacher will demonstrate a cartoon analysis each time from a different time period. Students reveal that they find analysing cartoons difficult because they do not know that much about those specific time periods. The knowledge test is poorly made and the teacher accuses the pupils of not being able to think critically.

New situation narrative: History in secondary school

The History teacher now starts his lesson by showing two cartoons, one of which is of Charlie Hebdo and one from the time of the Reformation. These cartoons depict with symbols the zeitgeist and debate in a specific context and time. Students are asked to analyse these cartoons and report their interpretation. This cartoon inquiry will be presented to each other in a poster format in a few weeks’ time. This lesson will use an example to show the teacher the elements of a cartoon analysis. The second half of this first lesson, students will have the opportunity to form groups of two and pick a time period and cartoon and formulate their research question. In future lessons, the teacher will walk around and give the opportunity to ask for brief instruction on parts of cartoon analysis. He will not instruct the whole class, but only small groups.

Old situation narrative: City ecology in higher education

The urban ecology course in the Biology program starts with a lecture in which the teacher explains the structure of the subject matter and lecture program. The relationship with other courses such as statistics, chemistry, and biodiversity is explained and the teacher indicates that this prior knowledge is presupposed. Everything can be found in Campbell’s Biology textbook, chapters must be studied and the subject concludes with an summative exam.

New situation case: City Ecology in higher education

The course City Ecology in the Biology program starts with an introductory meeting with two presentations in which last year’s students present their research on perennial mosses (licheen) on the quay walls of the Oude Rijn. The teacher points out that several new unexplored populations can be found in the city of Leiden. And then gives a brief instruction on setting up ecological research. The students will be tasked with conducting their own study of an organism in the city of Leiden. In the first lectures, students will receive tailored guidance on formulating a research question and designing their study. Adjacent, there will be guest lectures on ecological studies in other cities by students, PhD students, and postdocs. At the end of this lecture series, a student research conference will be organised in which staff members of the research institute and the students themselves will assess the students’ presentations.

Practical implications

We have developed practical tools for designing and delivering education in which subject matter is addressed in an inquiry-based way. These include both supervised inquiry-based learning of pupils and students and continuing professionalisation pathways in which (own) teaching is examined as part of initial and continuing teacher professionalisation. These tools are suitable for multiple teaching units: from learning objectives, design of lessons to curriculum lines.

Supporting learners and developing research skills

In this research, curriculum lines, modules and assessment forms have been worked out at several secondary schools on how to guide pupils in havo and vwo to do research independently, for instance for their profile paper.

Supervising teacher learning

- As continuing teacher professionalisation, we offer a module focusing on inquiry-based learning: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/cursussen/iclon/research-based-education

- Furthermore, you can talk to our experts about your curriculum, a subject or a teaching series in which you let pupils or students learn about the lesson/college material by doing research: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/iclon/higher-education/educational-advice/research-based-teaching-and-learning

- Perspectives (see building block perspectives) can play an important role in designing education in which pupils and students learn through enquiry. Below is a practical contribution on this for both academic education and secondary education: How can students learn to get a grip on complexity? – ScienceGuide (in Dutch)

- Janssen, F.J.J.M., Hulshof, H. & Van Veen, K. (2019). What is really worth teaching? A perspective-based approach. Leiden: StudioSB. (in Dutch)

Researcher/designer

- For evaluating research-based teaching and research in teaching, we have developed a ‘student evaluation of research in teaching’ questionnaire: Visser-Wijnveen, G.J., van der Rijst, R.M. & van Driel, J.H. (2018). A questionnaire to capture students’ perceptions of research integration in their courses. Higher Education volume 71, 473–488.

- In addition to this questionnaire, we have also developed a questionnaire that questions the ‘teacher evaluation of research in teaching’: Hu, Y., van der Rijst, R.M., van Veen, K. & Verloop, N. (2014). The Role of Research in Teaching: A Comparison of Teachers from Research Universities and those from Universities of Applied Sciences. Higher Education Policy volume 28, 535–554.

Educational leadership

Scholarly publications

- Hu, Y., van der Rijst, R. M., van Veen, K., & Verloop, N. (2019). Integrating research into language teaching: beliefs and perceptions of university teachers. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 56(5), 594-604.

Internationally, universities and policy-makers are calling for stronger integration of research into teaching. However, it is unclear how to implement this in practice in different disciplinary areas and contexts. This study contributes to this understanding with a focus on language teaching in the Chinese context. We surveyed 152 university teachers regarding their beliefs about and their perceived actual integration of research in their teaching practice. The teachers highly valued integration of research in teaching in an ideal situation but perceived low integration of research into their actual teaching practice. This gap was smaller for teachers from research-intensive universities and for those who had more research experience and spent more than 25% of their work time on research. Other reasons for this gap included fixed curricula, heavy teaching tasks, lack of student motivation and difficulties reconciling integration of research into teaching with the institutional aim of improving students’ language proficiency.

- Janssen, F.J.J.M., Vermeulen, M. & J.H. van Driel (2017) Leerprogressies voor bètadocenten. Ontwikkeling van expertise voor onderzoekend leren. Review studie. Leiden.

- Janssen, F.J.J.M., Westbroek, H.B. & van Driel, J.H. (2014). How to make guided discovery learning practical for student teachers. Instructional Science, 42, 67-90.

- Vereijken, M. W. C., van der Rijst, R. M, Dekker, F. W., & van Driel, J. H. (2020). Authentic research practices throughout the curriculum in medical education: student beliefs and perceptions. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 57(5), 532-542.

Opportunities for students to participate in research practices promote student beliefs about the relevance of research for later work practices. Yet engaging undergraduates in learning activities that mirror the way in which research is used in practice settings is not that straightforward. This longitudinal study aims to assess the influence of authentic research practices in the learning environment on medical undergraduates’ perceptions of research and their beliefs about the relevance of research. In total, 947 students completed the Student Perceptions of Research Integration Questionnaire. Our findings suggest that research practices promote student motivation for research and foster the belief that research is relevant to learning. We suggest that to foster student learning about research, it is beneficial to include elements of professional practices that stimulate students’ enthusiasm for research and focus students’ attention on the way research findings are produced. Furthermore, implications are given for further research and teaching practice.

- Visser-Wijnveen, G. J., van der Rijst, R. M., & van Driel, J. H. (2016). A questionnaire to capture students’ perceptions of research integration in their courses. Higher Education, 71,473-488.

Using a variety of research approaches and instruments, previous research has revealed what university students tend to see as benefits and disadvantages of the integration of research in teaching. In the present study, a questionnaire was developed on the basis of categorizations of the research–teaching nexus in the literature. The aim of the Student Perception of Research Integration Questionnaire (SPRIQ) is to determine the factors that capture the way students perceive research integration in their courses. The questionnaire was administered among 221 students from five different undergraduate courses at a research intensive university in The Netherlands. Data analysis revealed four factors regarding research integration: motivation, reflection, participation, and current research. These factors are correlated with students’ rating of the quality of the course and with their beliefs about the importance of research for their learning. Moreover, courses could be distinguished in terms of research intensiveness, from the student perspective, based on the above-mentioned factors. It is concluded that the SPRIQ helps to understand how students perceive research integration in specific courses and is a promising tool to give feedback to teachers and program managers who aim to strengthen links between research, teaching, and student learning.

Contact person for this principle

Roeland van der Rijst